An essential concept in consumer decision-making is that choices are made under constraints. Chiefly among these are having enough time and enough money, which are particularly pressing in today’s post-pandemic, inflationary climate.

As additional examples, limitations like dietary restrictions on ingredients such as salt, sugar, or gluten also constrain purchasing decisions.

However, a notable oversight of traditional Choice Based Conjoint Analysis (CBCA) as typically applied is its failure to account for any constraints whatsoever.

In particular, CBCA does not incorporate the buyer’s money budget into its price sensitivity estimations and predictions.

A new feature of the in4mation insights’ (i4i) choice modeling toolkit is Budget-Constrained CBCA (BC-CBCA) which operates on two straightforward assumptions:

-

- First, any product priced beyond an individual’s budget when presented in a conjoint survey, is disregarded, rendering its value null — no amount of brand prestige or appealing features can influence its selection. We do acknowledge that, in special situations, people will exceed their budget, yet not by that much, creating a new, slightly larger budget constraint.

- Second, for items within their budget, consumers exhibit relative price insensitivity, reasoning that, “If it’s within my budget, I can afford it.” BC-CBCA , as we apply this innovation, starkly contrasts with traditional CBCA by directly incorporating budget constraints into the decision-making process.

Consequently, price sensitivity for items under the budget limit is less pronounced. This leads to substantial differences in predicted overall choices between BC-CBCA and standard CBCA.

Importantly, in i4i’s BC-CBCA approach, the budget threshold does not have to be asked in the survey. Rather, it is estimated probabilistically based on participants’ choices within the context of the CBCA task. We note that the budget limit can be asked in the survey, but in that case it is a first approximation of what BC-CBCA will eventually calculate and use in estimation of the magnitude of all choice drivers.

An Example

Several years ago, we conducted a study looking at the choice of digital cameras. Roughly 450 prospective buyers replied to eight choice situations. Each situation had four brands or none to choose from. About ten attributes were investigated, including seven brands and prices that ranged from a low of $199 to a high of $459.

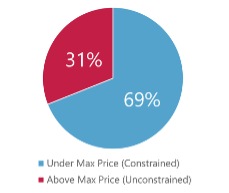

We counted the number of people who BC-CBCA estimated to be budget constrained; that is, they would not purchase a camera that cost more than the maximum price of $459. We found that about one-third have a budget greater than the maximum price shown in the survey (we call them unconstrained) and about two-thirds are budget constrained, meaning their budget limit is less than $459.

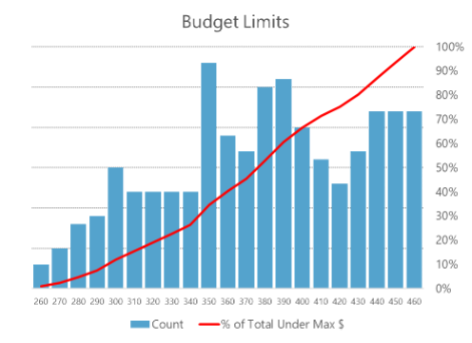

If we look only at those people who are constrained, we can estimate their maximum willingness to pay, in other words, their budget limit. Looking at this chart, you can see the percentage of people whose budget limit is at each of the bars, $10 at a time. The red line shows the cumulative percentage of people below the maximum price displayed, all of whom are budget constrained, but at different limits.

For example, the second blue bar from the left crosses the Y-axis at 20% indicating that percent of people have a budget limit that is $270 or smaller. If you mentally group the bars, you might say that there are three-four segments of people with budgets at different limits.

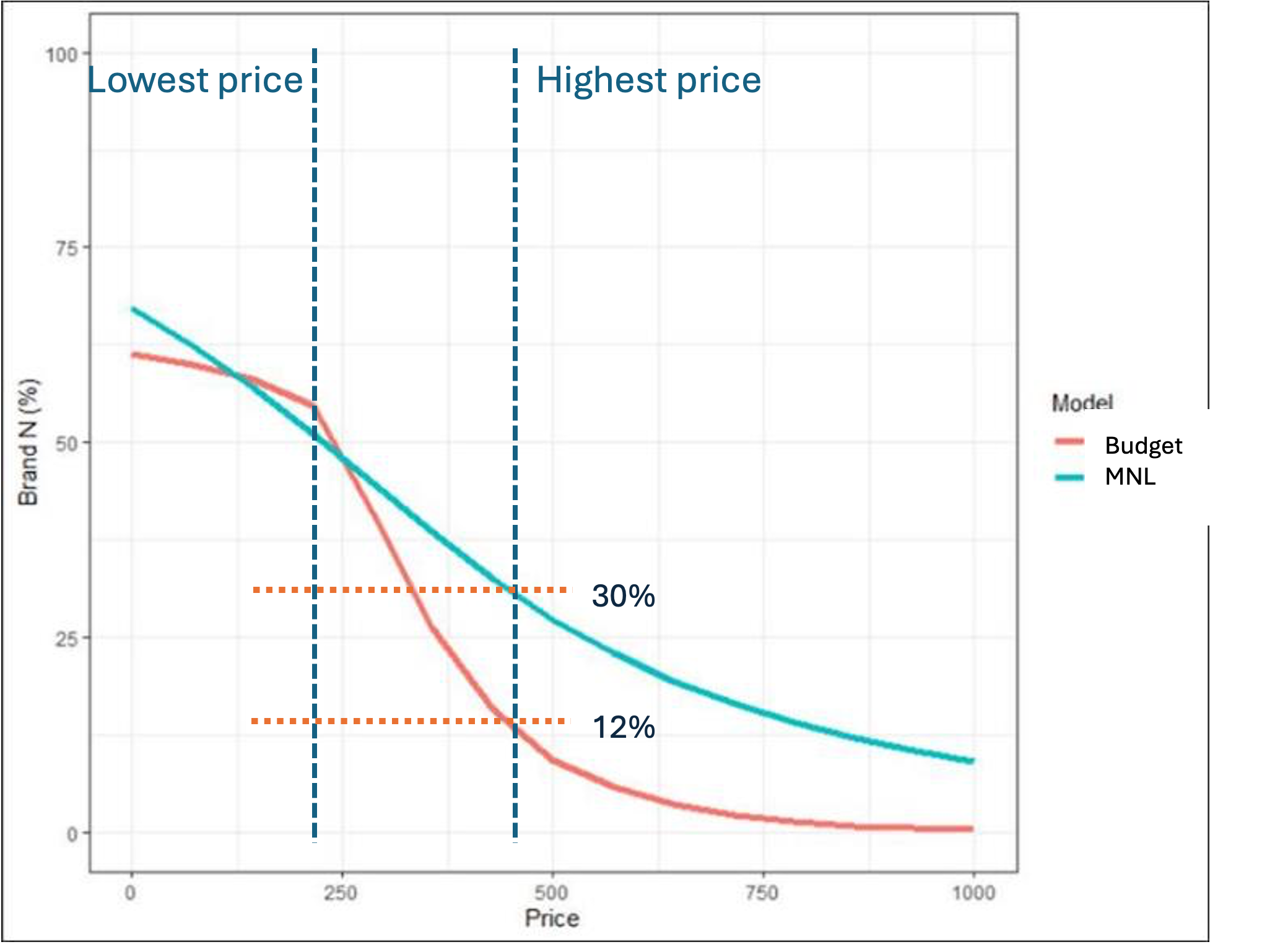

As previously mentioned, the constrained budget model yields a different price sensitivity than the standard approach does. To demonstrate this, we first created a “base case” of cameras with their features and prices. We chose camera brand “N” as our test of the price sensitivity. Displayed in this chart is the predicted choice share on the vertical Y-axis. The horizontal X-axis goes from $0 to $1000, although $199 was the lowest price evaluated across all brands and $459 was the highest price tested price. At the lowest price of $199, the two approaches – budget constrained and standard MNL –both predict a choice share of just over 50%. However, at the highest price evaluated, the standard approach predicts a choice share of 30% and the budget model predicts a little over 10%. Which seems more realistic and believable to you?

The budget constrained model has a much steeper price-choice curve. Why is that? As the price increases, the budget limit of individual people is being reached.

When the price exceeds their budget; the product becomes unaffordable and they “drop out” of buying that camera.

When the price exceeds their budget; the product becomes unaffordable and they “drop out” of buying that camera.

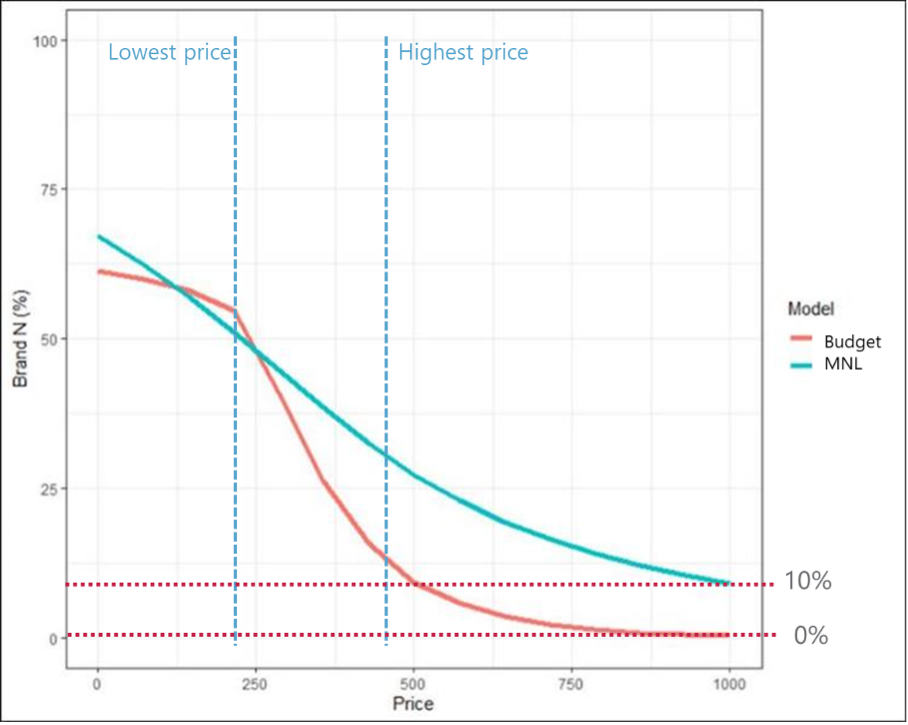

To show that the budget model will deliver more realistic results, we increased the price of camera N to $1000, as shown below. In this case, you will note that the standard MNL analytic model predicts that 10% of buyers will still chose Brand N – even at a price that is more than twice the maximum tested!

On the other hand, the budget constrained model delivers a more realistic result: no one will purchase at $1000, and in fact, the budget approach reaches 0% choosing “N” at around $800.

What is happening in the budget model versus standard multinominal logit (MNL) models? The standard only has one way to measure the effect of price (price sensitivity) while the budget constrained model has two ways (price sensitivity and a budget constraint). Since the standard model is “missing” the budget information, it increases the price sensitivity to make up for the fact that the budget limit is unknown.

Summary

Employing constraints in advanced CBCA offers more realistic predictions of buyer behavior across various categories, including hotel and travel selections, durable goods, electronics, premium products, and even groceries purchased at supermarkets. BC-CBCA distinguishes between individuals with financial constraints and those without, identifying segments of individuals with similar budgetary limitations.

This enables tailored product designs and offerings for different buyer groups with different constraints. Additionally, in BC-CBCA, we have observed that once the budget is accounted for, the role of price diminishes, and brand and product features play larger roles in influencing purchases.

Next Steps

BC-CBCA works. It produces deeper insights than the traditional approach.

We can show you.

We will even run BC-CBCA with your data from a standard CBCA project that you completed in the past.

That’s how sure we are of the power of BC-CBCA.

If you wish to fine tune your understanding of how consumers make choices regarding your products and services, by leveraging Budget Constrained – Choice Based Conjoint Analysis, contact us to discuss your challenges at info@in4ins.com.